The middle of five children, I grew up in a family that was wonderful in bringing Protestants and Catholics together, and this was long before Vatican II. My father was a Protestant and my mother a Catholic, and despite objections from both of their families, they built a good marriage. After leaving the farm in central Ohio, my Dad worked in Cleveland for a Jew, Max Friedman, who was, to mix religions, like Santa Claus to our family. This was all good. We weren’t so good, however, with African Americans.

The middle of five children, I grew up in a family that was wonderful in bringing Protestants and Catholics together, and this was long before Vatican II. My father was a Protestant and my mother a Catholic, and despite objections from both of their families, they built a good marriage. After leaving the farm in central Ohio, my Dad worked in Cleveland for a Jew, Max Friedman, who was, to mix religions, like Santa Claus to our family. This was all good. We weren’t so good, however, with African Americans.

When in the late 1950s my parents moved to their second home, we kept and rented out the first one. I remember one day answering the phone when a person asked whether the apartment was still available. I gave the phone to my mother. She told the caller that it was already rented. I knew it wasn’t. When she hung up, I asked her why she said that. She replied, “They wouldn’t be happy in our neighborhood.” I realized the “they” was an African American. I felt ashamed.

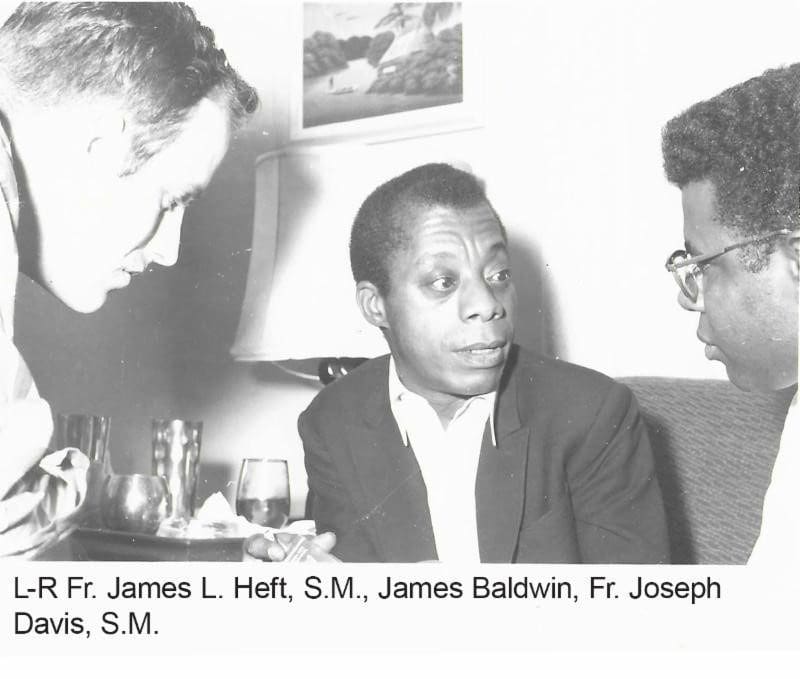

In the late 1960s, after entering the Marianists, I got involved in the civil rights movement, I read the Diary of  Malcolm X, Eldridge Cleaver’s Soul on Ice, and John Howard Griffin’s Black Like Me. One night in 1968, in Dayton, Ohio, I had an amazing two hour conversation with James Baldwin. I still have a picture of it. That same year, a bullet sailed through my office window one night. For those of us who lived through the late 60s, the times were tumultuous, demanding and sometimes dangerous. The civil rights and anti-war movements were important graces in my life.

Malcolm X, Eldridge Cleaver’s Soul on Ice, and John Howard Griffin’s Black Like Me. One night in 1968, in Dayton, Ohio, I had an amazing two hour conversation with James Baldwin. I still have a picture of it. That same year, a bullet sailed through my office window one night. For those of us who lived through the late 60s, the times were tumultuous, demanding and sometimes dangerous. The civil rights and anti-war movements were important graces in my life.

But one incident was especially poignant. At the newly built Marianist conference center, Bergamo, named after the birthplace of Pope John XXIII, I was running three-day retreats for seniors from several Catholic high schools. Three black students were on one of these retreats. The first evening and the next morning, it was obvious that they weren’t getting into the retreat at all. I asked them to come to my office and asked what the problem was. One replied, “This is all white middle-class stuff, and we don’t relate to it.” I thought for a minute, and then replied, “I am a middle-class white person, and it’s the best I can do.” One of them said, “We can do better.” I said, “Be my guest.”

I thought I’d never hear from them again. But six weeks later, they came back with a plan for a weekend retreat designed for both white and black students. That year, 1969, they ran six weekend programs. They were excellent programs, covering African American history, and small group interactions led by the black students. The only resistance to these programs came from some white families whose daughters wanted to attend. I learned that reading books by Cleaver and Baldwin didn’t compare with seeing talented black students lead and help their white peers understand the many forms of racism that shape our awareness, often without us realizing it. The students learned about the difference between personal and institutional racism, about being kind and working against injustices, and perhaps most importantly about reading about racism and forming friendships between races.

I recalled these events when I read the U. S. Bishops pastoral letter against racism, “Open Wide our Hearts: The Enduring Call to Love,” published in November of 2018. It is not the first time the U.S. Bishops have issued statements against racism. They did so in 1958, 1968, and 1979, each time identifying racism as a cancer, the “original sin” of the United States. This latest statement is noteworthy not only because it denounces racism, but also explains clearly how Church leaders have contributed to it. For example, Pope Nicholas V issued in 1452 a statement that gave permission for the kings of Spain and Portugal to buy and sell Africans. Later popes opposed the international slave trade, but the practice continued for centuries. In the United States some religious orders owned slaves, and even sold them in the 1830s to keep their university, Georgetown, from going bankrupt. This horrible list of support and complicity could be extended.

We all need to confront the structural injustices of our society, the ones that result in twice the number of black babies who, in comparison to white babies, die in the first year of their lives. We need to ask why, in 2016, 33% of the sentenced prison population was black while only 12% of the U.S. adult population is. Or why there continue to be differences between blacks and whites in pay, education, housing discrimination, mortgage lending, and even continuing school segregation. It is not enough to say that many black families are struggling and disadvantaged. We need to ask why they are, and how the history of racism has made their lives more difficult.

I end this reflection by asking you to read still one more, written by a fellow Marianist and dear friend, Bro. Raymond Fitz, S.M., who for over twenty years served as the president of the University of Dayton. He has spent a great deal of his life not just thinking about racism, but also working effectively against it. Dayton is one of the most racially divided cities in the country. He has done a great deal more on this than I have. I am attaching the text of a short presentation he made to a listening session of the Bishops’ Ad Hoc Committee on the Racism Pastoral. Please read it.

Blessings,

President, Institute for Advanced Catholic Studies

Conversion is Not Possible without Recognition of Our Sin

Bro. Raymond L. Fitz, S.M.

Fr. Ferree Professor of Social Justice

President Emeritus, University of Dayton

From Open Wide Ours Hearts, The United States Catholic Bishops Pastoral Letter Against Racism

From Open Wide Ours Hearts, The United States Catholic Bishops Pastoral Letter Against Racism

“What is needed, and what we are calling for, is a genuine conversion of heart, a conversion that will compel change, and the reform of our institutions and society.”

“All of us are in need of personal, ongoing conversion. Our churches and our civic and social institutions are in need of ongoing reform. If racism is confronted by addressing its causes and the injustice it produces, then healing can occur.”

“Love compels each of us to resist racism courageously. It requires us to reach out generously to the victims of this evil, to assist the conversion needed in those who still harbor racism, and to begin to change policies and structures that allow racism to persist.”

Open Wide Our Hearts issues a strong call for conversion by Catholics but does not name our sin — the Catholic community’s complicity in the social sin of racism. Without the recognition that we as Catholics have participated, perhaps unknowingly, in creating the social sin of racism there will be little or no motivation to undertake the journey to conversion of heart and the reforms needed in our civic, social, and Church institutions. The purpose of this reflection is two-fold. First, to illustrate some ways the Catholic community has contributed to the social sin of racism. Second, to outline briefly some elements in the Church’s program for regional racial justice and solidarity.

Over the past fifty years, most metropolitan regions throughout the country, especially in the East and Midwest, have become highly segregated economically and racially. Most often, these trends result in an architecture that has more affluent neighborhoods in the suburbs and disadvantaged neighborhoods in the center city. With rise of gentrification, there are some affluent neighborhoods in the center city. In every metropolitan regions, disadvantaged neighborhoods have a disproportionate concentration of people of color. Our metropolitan regions have become “fractured cities” with people in affluent neighborhoods and people in distressed neighborhoods having little connection and shared experience with one another.

In disadvantaged neighborhoods, there is a higher likelihood of children suffering adverse childhood experiences, i.e., physical, emotional, and sexual abuse, physical and emotional neglect, and dysfunctions in the household, such as lack of family stability, mental illness, and substance abuse. The toxic stress of living in poverty has a negative impact on the physical, cognitive, social-emotional, and spiritual development of children. These neighborhoods have a lack of child supportive resources, such as, high quality childcare and early learning, and effective PK-12 school experiences. Parents in disadvantaged neighborhoods often lack the resources, money and time, to read to their children and to provide enrichment activities like music lessons, organized sports, and travel. All of these factors create a significant gap between the opportunities available to children in affluent neighborhoods and the opportunities available to children in disadvantaged neighborhoods. In our disadvantaged neighborhoods, there exists a silent violence of poverty — it is a violent because it does serious harm to children and families. It is silent, because, many of us, especially those of us who live in white enclaves are indifferent to the suffering persons in disadvantaged neighborhoods. Addressing racial justice is just too complex and we move it to the periphery of our consciousness. Yes, some young people with the support of a parent or trusted mentor can develop the resilience to overcome this lack of opportunity, yet most young people in disadvantaged neighborhoods do not have these parents and trusted mentors.

The fracturing of our metropolitan regions and the resulting silent violence of poverty is an example of what the Catholic social tradition names as social sin. Multiple social structures, policies and practices contributed to the fracturing of our metropolitan regions. For example, the Residential Security Maps and Manuals created by the Home Owners’ Loan Corporation in the 1930’s discouraged lending to home-buyers that would upset the racial character of a neighborhood. These practices reduced access to mortgages in older and non-white neighborhoods. This practice affected whole neighborhoods, reducing owner occupancy, lowering property values decreasing housing quality and increased racial segregation. Other examples of this social sin are the restrictive zoning codes designed to keep certain racial groups from being part of a suburban neighborhood. In addition, the block busting strategies of some real estate agents cause uncertainty and churn in center city neighborhoods contributing to racial segregation and growth of disadvantaged neighborhoods. Many of these sinful social structure privilege “whiteness” because these social structures give greater access to opportunities to white persons and households. These same regional social structures place many barriers to opportunities for people of color.

Two factors influence the creation of these sinful social structures, one personal and one cultural. The first factor are the acts of greed, deception, and prejudice by people responsible for the social policies and practices outline above. A second factor is the culture of our regional communities. Our dominate culture has a strong theme of individualism where person make personal and family decisions based solely on their best interest. Very often, these decisions are made without considering the impact on the good of the community as a whole.

I believe we, as a Church, need to address the question “Does our Catholic community have complicity in the social sin of racism? Research from the archives of several Dioceses shows that the Catholic households moved from the center city at a rate that is higher than the rate of households in the general population. Economic success of the Catholic population fueled this movement. A tradition of stable families and good education, often in Catholic schools, were major factors in this economic success. These factors positioned Catholics to take advantage of the GI Bill, the growth of higher education, and the growth of family supportive jobs. With the promise of larger homes and yards, better schools, and safer neighborhoods, one can easily understand why many Catholic families with economic means moved out from the center city.

This movement by the Catholic population to the suburbs precipitated a shifting of the resources of the Church e.g., Catholic parishes and schools, from the center city to the suburbs. In the past twenty years, most Dioceses have seen the closure of parishes and school in the center city neighborhoods. For many reason, Catholic sponsored hospitals have disappeared from the center city without much public protest by the pastoral leaders of the Catholic community. Today there is a greatly diminished Catholic presence in disadvantaged neighborhoods, especially neighborhoods of color. This shift gives the Church diminished resources to address the silent violence of poverty in these neighborhoods. We as a Church must come to terms of how this movement of Catholic families and resource to the suburbs has contributed, perhaps indirectly, to the fracturing of our metropolitan region and to the silent violence of poverty of disadvantaged neighborhoods.

I can understand why the Bishops did not use “white privilege” in the Pastoral Letter; it could be unnecessarily inflammatory. Yet, I do not believe that we can avoid “the difficult conversations” with the white privilege that many of us Catholics have experienced if we are to take the journey to conversion called for by the Open Wide Our Heart. Does our Catholic faith give us the motivation and courage to undertake this journey? The conversion called for in Open Wide Our Hearts can only come from recognizing our complicity in the social sin of racism, by repentance and seeking forgiveness, and becoming a vigorous catalyst and partner with others for racial justice and regional solidarity.

I conclude this reflection by outlining briefly five recommendations that can contribute to the Catholic Church becoming a catalyst and partner in overcoming racial injustice and creating regional solidarity.

1. Develop an Appreciation of the Social Sin of Racism in our Metropolitan Regions.

The Pastoral contains the challenge “Racism can only end if we contend with the policies and institutional barriers that perpetuated and preserve the inequality — economic and social — that we still see all around us.” The United States Conference of Catholic Bishop has developed good resources for examining and contending with systematic racism. Integrating these resources into the curriculum of our Catholic Schools and Universities and our parish adult education programs is imperative. These programs must not only conduct social analysis of racial injustice in a given metropolitan region but must touch the hearts of Catholics by examining our implicit bias of white privilege and our personal contributions to the structures of racial injustice.

2. Rebuild or Sustain a Catholic Urban Presence in One or More Disadvantaged Neighborhood of the metropolitan region.

One important element in the Church’s effort to combat systematic racism would be the rebuilding or sustaining a Catholic presence in one or more disadvantaged neighborhoods with a high percentage of people of color. This Catholic presence could serve one or more of the following purposes:

- To provide children with an education pathway that could include child-care, quality early learning and excellent primary education;

- To provide parents with the knowledge and skills needed to build strong families, support their children’s learning, develop economic self-sufficiency;

- To partner with people of the neighborhood in organizing the assets of their neighborhood and developing programs that will improve the quality of life;

- To provide an evangelizing outreach in the neighborhood; and

- To provide the experience of hospitality and dialogue for members of the regional Church to share experiences and stories.

3. Bridge and Heal the Fractured Regional Church.

Our metropolitan region is fractured and often our regional Catholic Church is fractured. Pew Research illustrates that the Catholic Church nearly mirrors the fractured nature of our larger society. There is a major gap between the experience Catholics in the suburbs and the experience of Catholics and others in disadvantage neighborhoods of color. The regional Church has made some efforts to bridge and heal these fractures. For example, there has been the twinning of parishes within metropolitan regions. In my judgement, a more comprehensive effort is required.

The Catholic urban presence, outline above, can be a site to host opportunities for conversations among people of the different neighborhoods in which they share personal experiences and stories. Out of these conversations, friendship can grow, providing a starting point for healing, reconciliation, and common action. Creating spaces for encounter and dialogue where people of diverse experiences can come together in encounter and dialogue is critical for racial healing within the metropolitan region.

4. Create and Participate in Forums of Public Deliberations on the Common Good

To be a catalyst and partner in creating racial reconciliation and healing requires that Catholics participate in public deliberations on the common good with knowledge, civility and compassion. Public discourse in our country is often highly polarized and this discourse cannot create a consensus on away to enhance the common good. Parishes and regional offices of Catholic social action and Catholic Charities should develop educational programs that help Catholics develop the skills to participate in public deliberation in a way that creates greater consensus across differences. These educational programs must incorporate the best practice skills of hosting and facilitating encounter and dialogue with the insights of our Catholic social tradition. The Catholic Church, along with other faith communities, can create spaces for encounter and dialogue in which the hard work can be done of understanding racial injustice within the region, creatively imagining a new future of greater racial justice, designing strategies to bring about this new future, and organizing people and resources to implement the strategies. Only with serious Catholic engagement in public deliberation, along with other persons and groups of faith and good will, will the message of Open Wide Our Hearts be a catalyst for a movement toward racial justice and solidarity with in our metropolitan regions.

5. Create a post-parochial financial strategy to support these efforts of healing and reconciliation.

In the past the Catholic Church has pursued a parochial financial strategy, i.e., if a parish cannot develop the resources to support its sacramental and pastoral ministry, then the leadership of the diocese will make a decision to close it or merged with another parish. There have been many innovative efforts to go beyond this parochial financial strategy. Yet, if our Church is going to be a catalyst and partner in healing the racial injustice and creating a strategies transformation that bring about a greater realization of the common good, then our Church must develop post-parochial financial strategies that will support this effort. These strategies will demand that we as Catholics stretch ourselves to be more generous in supporting the Church’s task of promoting racial justice and solidarity with the metropolitan region.

In summary, to realize the intent of Open Wide Our Hearts, we as a Catholic community must recognize our complicity in the social sin of racism, seek ways of forgiveness and healing, and become a catalyst and partner in the social transformation required for greater racial justice and regional solidarity.