The story of Catholicism in South Pasadena predates the establishment of our beloved church. The modern Monterey Road once served as a vital connection between Mission San Gabriel and the new settlement of Los Angeles. On the Arroyo, a tree known as the Cathedral Oak bore a crude cross carved into its bark, marking a historic site where Mass was celebrated during Gaspar de Portolá’s expedition of 1768 or 1770. Tradition holds that one of the Franciscan chaplains, Fr. Francisco Gomez or Fr. Juan Crespi, celebrated the first Mass in what is now South Pasadena. In honor of this moment, an oak tree was planted on the Diamond Jubilee of Holy Family Parish at the site of that first

It wasn’t until 1906 that land was purchased for a Catholic church in South Pasadena. Bishop Thomas J. Conaty assigned Rev. Richard J. Cotter, D.D., the task of establishing the parish on property located at El Centro Street and Fremont Avenue. The first Mass was celebrated in a small cottage on the corner of El Centro and Fremont on May 10, 1910. At that time, the parish boundaries extended from Columbia Avenue to the north, Alhambra Road to the south, Garfield Avenue to the east, and Arroyo Drive to the west.

It wasn’t until 1906 that land was purchased for a Catholic church in South Pasadena. Bishop Thomas J. Conaty assigned Rev. Richard J. Cotter, D.D., the task of establishing the parish on property located at El Centro Street and Fremont Avenue. The first Mass was celebrated in a small cottage on the corner of El Centro and Fremont on May 10, 1910. At that time, the parish boundaries extended from Columbia Avenue to the north, Alhambra Road to the south, Garfield Avenue to the east, and Arroyo Drive to the west.

The parish grew rapidly, necessitating a larger church. On November 24, 1923, land at Fremont Avenue and Rollin Street was acquired for the construction of a new church. With limited funds, the original building on El Centro was moved to the new site. Finally, during the Easter season of 1928, the church on Fremont and Rollin was dedicated, solidifying its place as the heart of Catholic life in South Pasadena.

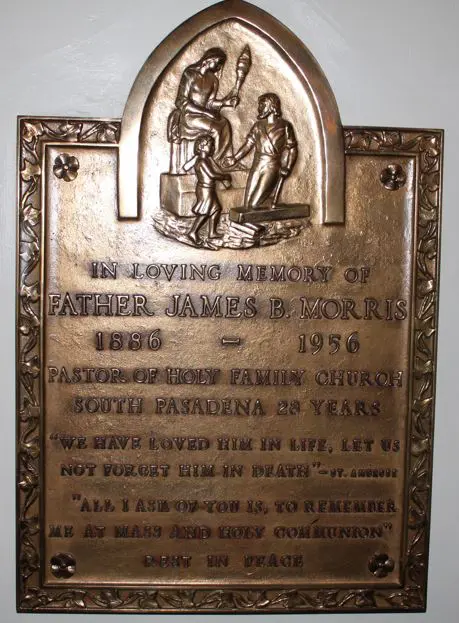

1926, Fr. James B. Morris, whose plaque is displayed in the church vestibule, was assigned to Holy Family with the mission of raising funds to build a new church. To achieve this, he organized annual three-day bazaars, picnics, barbecues, card parties, and dinner dances—early predecessors of today’s parish auction.

The plaque in his honor states:

“Four years after the purchase of the property, construction began in 1927.”

The proposed budget for the new church was $10,000. Emmet G. Martin, a renowned Southern California architect celebrated for his Renaissance-Baroque designs, was chosen to design the building. Construction was carried out by the Charles W. Pettifer Company.

On Easter Sunday, 1928, the first Masses were celebrated in the new Holy Family Church. Solemn Masses were held at 6:00 a.m. and 10:30 a.m., while Low Masses were celebrated at 8:00 a.m. and 9:00 a.m. Father James B. Morris, rector of the church, officiated at all the services.

The formal dedication of the church took place two weeks later, on Sunday, April 22, 1928. The event featured Catholic dignitaries and over a hundred visiting priests who participated in the Solemn High Mass and dedication ceremony. Rt. Rev. Joseph J. Cantwell, Bishop of Los Angeles and San Diego, returned to dedicate the church. The celebration included a procession around the church and the blessing of the structure.

In his dedicatory address, Bishop Cantwell praised the parish and its rector, Fr. Morris, for their remarkable accomplishment. He described the newly erected church as a “monument worthy of the beauty of its environment.”

The church’s environment in 1928 was quite different from today. Holy Family Church originally featured hardwood floors throughout. Its windows were simple, with nearly clear glass. The reredos was made of stained wood, adorned with lifelike statues in its niches, and the altar was positioned directly against it. A communion rail separated the sanctuary from the nave. The dark mahogany pews, carved with the symbols of a cross, heart, and crown, remain in the church today, though they have been stripped and restored multiple times over the years.

Whether in 1928 or now, Holy Family Church has always been a sacred space, inviting all to enter for prayer, rest, worship, and community, truly embodying its role as a place to become Church.

Holy Family Church reflects the Spanish Baroque style, characterized by a high concentration of carved stone ornaments, particularly around the entrance portals and the north and south transepts above the windows. The façade features bronze statues of the Holy Family and two stone bas-relief medallions depicting moments from Jesus’ boyhood.

Towering 90 feet above Rollin Street, the church’s Moorish tile dome is capped with an intricately carved stone ornament.

The Church as a Sacred Space

When we speak of the Church, we often refer to the people of God. However, the church building itself holds profound significance. The word “church” derives from the Greek kuriakos (“of the Lord”). These physical structures are more than gathering places; they symbolize the Church living in a particular community—the dwelling of God with His people, reconciled and united in Christ.

Entering a church means crossing a threshold, symbolizing the passage from a world wounded by sin to the new life offered in Christ. The visible church is a symbol of the Father’s house, where the faithful journey toward God, who will wipe away every tear. Historically, churches have also served as places of assembly, hospitals for the sick, and sanctuaries for the oppressed—always spaces of comfort and solace.

The Reredos

One of the most noticeable features of the church is the reredos behind the altar. The term “reredos” (or retable) originates from the Latin words retro (behind) and tabula (table), referring to the set of figures or scenes placed on an architectural structure behind the altar. This feature highlights the sacred nature of the altar and serves as a focal point for religious ceremonies.

The reredos became prominent during the Gothic period, evolving in response to the desire to emphasize the sacredness of the altar through religious imagery. Particularly developed in Spain, early reredoses in the 11th and 12th centuries were crafted from gold, silver, or ivory and adorned with relief sculptures. By the late Gothic period in England and the Renaissance in Spain, reredoses became permanent architectural features.

Holy Family’s reredos is similar to those found in Spain. While primarily ornamental, it incorporates significant Christian symbols:

- At the top, a cross represents Christianity’s central symbol.

- Below the cross, a dove symbolizes the Holy Spirit.

- Above the dove is a crown, representing Christ as King.

- The coat of arms of St. Patrick (left) and St. Columbkille (right) are displayed above their respective statues.

The center niche of the reredos stands out as unique. In 1992, Fr. Mike Wakefield rediscovered the original crucifix, hidden in an office, and collaborated with Msgr. Connolly to restore it. They uncovered and restored the center niche, which had been concealed when the tabernacle was moved to the side altar. The niche was gold-leafed and adorned with angel faces, and the restored crucifix was placed within it.

The reredos also features the Holy Family in color relief, depicting them at work. This original artwork remains a beautiful highlight of the altar.

The reredos includes pewter statues of St. Patrick (left) and St. Columbkille (right). These saints were likely chosen by Fr. Morris, the pastor who raised funds for the church. St. Patrick represents the Irish Catholic Church, while St. Columbkille reflects Fr. Morris’ personal connection to his home parish in Ireland, also dedicated to St. Columbkille.

St. Columbkille

St. Columbkille (also known as St. Columba) was born around 521 in Gartan, Donegal, Ireland, into a royal family. He studied in Moville and Clonard, where he was ordained a deacon and later a priest. Columbkille founded several Irish monasteries, including those in Derry, Durrow, and Kells.

A feud between his clan and King Diarmaid resulted in the deaths of 3,000 people. In response, St. Columbkille left Ireland as penance, vowing to convert an equal number of pagans.

In 563, he traveled to Iona, off the coast of Scotland, with twelve relatives. There, he established a monastery that became one of Christendom’s most influential. Columbkille evangelized the Picts, converting their king, Brude, at Inverness.

In 575, he attended the Synod of Drumceat in Ireland and advocated for women’s exemption from military service. His contributions to Western Christianity were vast. The monastic rule he developed was widely practiced across Europe until it was eventually supplanted by the Rule of St. Benedict.

Let us now turn our attention to the other “Irish” saint—St. Patrick. According to Anita McSorley, some of the popular legends surrounding St. Patrick may not hold up to historical scrutiny. He likely didn’t chase snakes out of Ireland, and there’s little evidence that he used a shamrock to teach the mystery of the Trinity. Yet St. Patrick deserves immense honor—not only from the people of Ireland but also from all those who have experienced oppression or exclusion.

What we do know about St. Patrick is far more compelling than the myths. Born as Patricius in Roman Britain to a relatively wealthy family, Patrick was not particularly religious in his youth. In fact, he admits to having nearly renounced the faith of his family. However, his life changed dramatically when, as a teenager, he was kidnapped during a raid, transported to Ireland, and enslaved by a local warlord. For six years, Patrick worked as a shepherd, enduring hardship and isolation, before successfully escaping back to his homeland.

After returning home, Patrick felt a divine calling. He began studying for the priesthood with the intent of returning to Ireland as a missionary to his former captors. Although the details of his mission—such as when he returned to Ireland and for how long—remain unclear, his influence over several years was profound.

The Magnificent Murals of Our Church

Our church is blessed with two magnificent murals above the side altars, painted in 1951 by the father-daughter team Hector and Judith Serbaroli. These works of art add beauty and depth to the spiritual atmosphere of our sanctuary.

- On the left, we see the poignant scene of St. Joseph on his deathbed, with Jesus and Mary lovingly by his side.

- On the right, we have the Assumption and Coronation of Mary in Heaven, a glorious depiction of Mary’s entrance into eternal glory.

Hector Serbaroli, a renowned Italian artist with murals in several churches, designed these works with the help of his daughter, Judith. The Assumption mural was generously donated by the Altar Society, and in 1984, it was restored, with the faces of the angels painted to resemble children from Holy Family School.

About Hector Serbaroli

Hector Serbaroli, born in Italy, was a highly skilled artist who attended St. Michael’s Institute of Art in Rome and later St. Luke’s Academy. In 1902, he and five other artists were sent to Mexico City to work on three churches, but the Mexican Revolution interrupted this endeavor. During his time in Mexico, he met his wife, and the couple eventually moved to San Francisco before settling in Southern California, where Hector worked in the motion picture industry.

Judith, Hector’s daughter, began assisting him at the age of seven. By the time they were commissioned to create the murals at Holy Family, Judith was an accomplished artist in her own right.

The Murals in Detail

- The Death of St. Joseph (Left Mural):

This mural portrays the peaceful passing of St. Joseph, surrounded by Jesus and Mary. St. Joseph is often invoked as the patron of a happy death, and Serbaroli captures this theme beautifully. Light emanates from above, symbolizing the departure of St. Joseph’s soul, as if it has taken flight. This serene and spiritually rich depiction was a generous donation from Mr. and Mrs. Otto Beck. - The Assumption and Coronation of Mary (Right Mural):

This mural celebrates Mary’s Assumption into heaven and her Coronation as Queen of Heaven. The vibrant imagery and heavenly details reflect the glory of this event, a central belief of the Church and a reminder of Mary’s unique role in salvation history.

The Altar of Holy Family Church

The word “altar” originates from the Latin word altare, derived from adolere (to burn), and came to signify the table on which the bread and wine for the Eucharist are placed.

Holy Family Church’s altar is original to the building and is made of marble. In its early days, the altar was positioned against the reredos and was about 20% larger than it is today. The original design included additional decorative elements, such as:

- A round mosaic at the center featuring a ciborium, a host, and wheat against a blue background, adorned with golden filigree. Which is still in the center front of the altar.

- Golden Alpha (Α) and Omega (Ω) symbols on either side of the mosaic, symbolizing Christ as the beginning and the end. These were removed when the altar was moved.

During the 1970s, the altar was moved to align with the directives in the Roman Missal, which called for the presider to face the congregation during the Eucharistic prayer. Unfortunately, part of the altar broke during the move, resulting in its reduction in size. The tabernacle, originally positioned at the center of the altar against the reredos, was replaced with a new one, now located on the side altar.

The Altar Stone and Relics

Holy Family’s altar includes an altar stone, a traditional component of Catholic altars. Although no longer a prerequisite, the altar stone remains an important symbol of the Church’s heritage. The stone is embedded within the altar and flush with its surface, bearing a single engraved cross. It contains sealed relics of a martyr or saint, a practice that underscores the Church’s connection to the communion of saints.

The relics within Holy Family’s altar stone—and those in over 90% of altar stones in Southern California—are of Saint Candidus, a member of the Theban Legion.

The Story of Saint Candidus

According to historian Alban Butler, Candidus was a senator militum (leader of soldiers) within the Theban Legion, a group of Christian soldiers recruited by Emperor Maximian Herculius in Upper Egypt to suppress the rebellious Gauls known as the Bagaudae.

When Maximian commanded his soldiers to offer sacrifices to pagan gods for the success of their campaign, the Theban Legion refused, citing their loyalty to the true God. Candidus, as one of their leaders, declared:

“We are your soldiers, but we are also servants of the true God. We cannot renounce Him who is our Creator and Master—and yours, even though you reject Him.”

Unable to sway their resolve, Maximian ordered the execution of the entire legion. This mass martyrdom took place near Agaunum (modern-day Saint-Maurice, Switzerland) in 287 A.D. The Church commemorates Candidus and his companions on September 22nd in the Roman Martyrology.

For centuries, the principal relics of Candidus and the Theban Legion were preserved at the Abbey of Saint-Maurice, founded by St. Theodore of Octodurum in the 6th century.

The Presider’s Chair

Between the reredos and the altar stands the presider’s chair, an essential furnishing symbolizing leadership in worship. The word “chair” traces its origin to the Latin cathedra, which referred to the seat of a high-ranking civic official. Early Christians adopted this term to designate the bishop’s chair, from which he presided over the liturgy and preached. Other chairs (sedilia) for priests and deacons were placed to the side.

Over time, church architecture elevated the bishop’s cathedra on a podium, making it more throne-like. By the fourth century, as parishes developed, priests used simpler chairs, as most liturgical actions were conducted at the altar. However, the liturgical reforms of the 20th century sought to recover the significance of the presider’s chair.

Today, the presider’s chair reflects the dignity and service of Christian ministry. Its materials and design align with the church’s style, emphasizing prayer leadership rather than privilege. From this chair, the presider calls the assembly to prayer, leads moments of silence, proclaims intercessions, and blesses the congregation. Although rare for priests, preaching from the chair is also permitted by liturgical rubrics.

At Holy Family Church, the presider’s chair was donated by Estella Dohey, a generous benefactor.

The Side Altars and Reredos

In 1950, Holy Family Church expanded its furnishings to include two side altars, funded by parishioners who had recently completed the school building. C.M. Gilbride oversaw the construction, which was completed by Easter of that year at a cost of $10,188.00.

The side altars’ reredos are carved from Philippine mahogany, featuring a grapevine motif, symbolizing the Eucharist and the fruitful connection to Christ. Side altars are traditionally devotional spaces, often dedicated to saints or specific spiritual needs.

- Left Side Altar (Mary):

The left altar was likely dedicated to Our Lady, as suggested by the mural above, depicting Mary’s Assumption and Coronation in heaven. However, any carved appointments on this altar have been lost over time due to renovations.

This altar now serves as the altar of repose, housing the tabernacle, which contains consecrated hosts for the sick and homebound and for adoration. The current tabernacle replaced the original, which was damaged during its removal in the 1970s. The word “tabernacle” derives from the Latin for “tent,” recalling the Jewish tent that housed the Ark of the Covenant. Above the tabernacle, a brass lamb symbolizes Christ, the Lamb of God, who is the perfect sacrifice.

- Right Side Altar (St. Joseph):

This altar is likely dedicated to St. Joseph, as indicated by the carpenter’s square and three lilies carved into its face—symbols commonly associated with him. The mural above depicts the Happy Death of St. Joseph, painted a year later.

The right altar also houses the ambry (Latin for “cupboard” or “chest”), used to store the oils for sacraments. The ambry at Holy Family is the original tabernacle from the little wooden church on El Centro. It was restored in the 1990s by parishioner Tony Fortner, who added a glass window. A brass depiction of the Holy Spirit is mounted above the ambry, reflecting the proximity of this altar to the baptismal font.

The Sanctuary Lamp

The sanctuary lamp, a silent witness to the Eucharist, burns near the altar. Holy Family’s current lamp was purchased in 1999 and securely mounted to the wall to prevent accidents during earthquakes. This precaution ensures the lamp will not slide off and potentially cause a fire.

The Ambo and Its Significance

In earlier times, the large podium in churches was referred to as the pulpit, but today, it is commonly called the ambo. The word “ambo” originates from the Greek verb anabainein (“to go up”) and was the term used for the elevated platform where Scriptures were proclaimed in the grand churches of the early Middle Ages.

At Holy Family Church, the original ambo remains a cherished fixture, though it has undergone several improvements over the years. Made from mahogany, like much of the church’s woodwork, the ambo is octagonal in shape, featuring three steps leading to its landing. Its intricate design includes eight carved cherub faces and eight crosses, symbolizing divine presence.

The ambo has been moved several times throughout its history but now resides permanently on the left side of the sanctuary. The pedestal supporting it has been renewed and enhanced in the 1990s. Inside the ambo are tools to assist lectors and presiders, including a stationary bookrest, shelves for additional books, and a directional microphone.

A beautifully crafted and proportioned ambo is more than just a piece of furniture; it is a cradle for the Word, embodying the story of salvation and the mystery of the Word made flesh.

The Alcoves and Shrines

Our Lady of Perpetual Help Alcove

Near the front of the church, the shrine to Our Lady of Perpetual Help features a mosaic gifted in 1987 by LeRoy J. Borowicz in honor of his mother, Estelle Williams Borowicz.

The original icon of Our Lady of Perpetual Help is believed to date back to St. Luke, who, according to tradition, painted it during Mary’s lifetime. The icon was venerated in Constantinople for a millennium before disappearing during the city’s fall in 1453. Its image depicts Mary offering maternal protection to the frightened Christ Child, who has run to her so quickly that His sandal dangles from His foot. Above them, the Archangels Michael and Gabriel hold the instruments of His Crucifixion.

Because Our Lady of Perpetual Help is the national patroness of Haiti, the Haiti Ministry at Holy Family Church has dedicated this sacred space to honor her and raise awareness about the lives and struggles of the Haitian people.

The alcove not only features the mosaic of Our Lady of Perpetual Help but also displays various pieces of Haitian art, reflecting the vibrant culture and deep spirituality of the nation. These works of art, crafted by Haitian artists, capture the resilience and faith of a people who have endured immense challenges.

Additionally, the ministry has included informative displays that shed light on the realities of life in Haiti during this era. These displays offer parishioners and visitors an opportunity to learn about the social, economic, and environmental hardships faced by Haitians, as well as the strength and hope that define their communities.

Through this alcove, the Haiti Ministry seeks to inspire solidarity, prayer, and action, inviting all to join in supporting the people of Haiti through faith, awareness, and compassion.

The shrine also houses the Book of the Sick, where names of those in need of prayer are written—a reminder of Mary’s intercession and care for all her children.

The Holy Family Alcove

The Holy Family Alcove, featuring a wood carving gifted by Andrea and Frances LaRussa. Inspired by Cardinal Manning’s admiration for the piece, Mrs. LaRussa felt it symbolized her grandparents. The carving portrays a young Holy Family: Joseph teaching Jesus carpentry while Mary looks on, engaged in needlework.

Each alcove also houses tables that conceal part of the church’s sound system, producing the deep, resonant tones that enhance worship.

Our Lady of Guadalupe Alcove

In the early 2000s, parishioner and Biblical Scholar, David Sanchez initiated a heartfelt campaign to bring an image of Our Lady of Guadalupe, the beloved Patroness of the Americas, into our church. His vision culminated in the commissioning of Lalo Garcia, a celebrated artist, to create a painting of Our Lady of Guadalupe. This artwork beautifully depicts her image as it appeared on the tilma of St. Juan Diego, the miraculous cloth that bears her sacred imprint.

Lalo Garcia is renowned for his contributions to cultural arts in Southern California. As a principal artist and consultant, he has enriched communities through his work on numerous cultural programs and events. Garcia has led workshops for children and adults in collaboration with organizations such as the Autry National Museum, the Southwest Museum, and community celebrations including Día de los Muertos, Mexican Independence Day, and Our Lady of Guadalupe Feast Day. His art reflects a deep reverence for faith, culture, and heritage, making him an inspired choice for this commission.

The painting was formally dedicated in a solemn ceremony graced by the presence of Archbishop José H. Gomez. His participation underscored the importance of Our Lady of Guadalupe as a unifying and inspirational figure for the parish and the wider community.

This stunning portrayal of Our Lady now holds a prominent place in the church, inviting all who enter to reflect on her message of love, hope, and intercession for all her children. The painting serves not only as a devotional image but also as a reminder of the enduring faith and cultural heritage that enriches our parish family.

The Stations of the Cross

Arranged along the church’s interior walls are fourteen Stations of the Cross, each depicting an event in Christ’s journey from His condemnation to His burial. This devotional tradition began as a way for those unable to travel to Jerusalem to follow the Via Dolorosa. The Stations at Holy Family are plaster reliefs adorned with intricate ornamental designs, each marked with a Roman numeral below and a cross above.

In the early 2010s, it became evident that the Stations of the Cross were in poor condition. Theresa Cardinelli, a devoted parishioner, undertook the meticulous task of restoring them. She carefully cleaned each station and repaired damaged plaster by creating molds and recasting the missing pieces, restoring them to their original luster.

Once Theresa completed her restoration, the Ministry of the Arts painted the figures and backgrounds. A striking feature of their work is the gradual shift in the sky’s tone throughout the stations. For example, the background of Station 1 is approximately 14 times lighter than that of Station 14, transitioning from a bright blue morning sky to the deep hues of dusk.

The Paschal Candle

The Paschal Candle is placed in a beautifully crafted stand that complements the ambo and other wooden elements in the church. Standing at about four and a half feet tall, the stand cradles the candle, which descends approximately 12 inches into it. The decoration on the stand is largely ornamental. This Candle Stand was a gift in thanksgiving for the restored health of a child in 1994.

Throughout the Easter season, the Paschal Candle remains near the ambo. Afterward, it is moved to the area by the baptistery, where it continues to symbolize the Light of Christ at both funerals and baptisms throughout the year. Holy Water and Baptismal Fonts

Baptism is one of the most sacred and significant sacraments in the Church. Its roots lie in the baptism of Jesus by John and are deeply connected to the theology expressed by St. Paul: “Do you not know that all of us who were baptized into Christ Jesus were baptized into his death? Therefore we have been buried with him by baptism into death, so that, just as Christ was raised from the dead by the glory of the Father, we too might walk in newness of life.” (Romans 6:1–4)

Holy Water and Baptismal Fonts

On a Sunday morning, as parishioners rush into church, they are greeted warmly by the usher at the door. But what else do they encounter? Yes, they dip their hands into the Holy Water Font and sign themselves, recalling their baptism. The main Holy Water Font, located near the Fremont doors, is the original baptismal font. It was restored in the 2010s, ensuring its service for another hundred years. Smaller marble and metal fonts are found at other entrances to the nave of the church.

The earliest evidence of dedicated baptismal spaces dates back to the third century, discovered in a house church in what is now Syria. By the fourth century, baptistries—buildings specifically dedicated to baptism—became common. Holy Family Church once had a baptistery, though it is no longer used for baptisms following the liturgical changes introduced by Vatican II. The original baptistery has since been repurposed as the reconciliation room, located in the Fremont vestibule. Inside this room, the original gate can still be seen. Upon closer inspection of the Iron Gate, an image of an infant is visible at its center.

The word “baptize” means “to dip,” and “immersion” refers to the practice of submerging the body in water. However, early fonts were likely too small to allow for full immersion. As infant baptism became more common, baptismal fonts grew smaller and were often moved from the baptistery to the main body of the church.

Following the liturgical reforms of Vatican II, the placement of baptismal fonts within the church was recommended. In Easter of 1990, the current baptismal font was introduced. Designed to match the marble and woodwork of the church, this octagonal font features a copper basin. It has since served as the site for most baptisms. One of the eight panels on the base contains a door revealing the plumbing, with warm water used to ensure the comfort of infants and children during baptisms.

To accommodate the font, the side altar platform was enlarged, and great care was taken to match the marble work with the existing design of the church. Nearby, the ambry holds the sacred oils used for Baptism, Confirmation, Ordination, and the Sacrament of the Sick.

During the Easter season, a portable font is placed in the sanctuary to allow for baptisms of adults at the Easter Vigil. This larger, pool-like structure enables adult candidates for baptism to step into the water.

Bells

You may have noticed that Easter, our “Alleluia” time, is also a season when we ring more bells. Bells have been an integral part of Catholic worship for centuries. During the liturgy, the altar servers ring the hand bells, also known as “sanctus bells,” twice at each elevation of the Eucharist. From the sixth century until the liturgical reforms, bells were rung five or six times during Mass. The hand bells used at Holy Family appear to be original to the church.

In addition to the hand bells, Holy Family is blessed with bells that call to the wider community. Three Carillon Chimes were installed as a gift to honor the nation’s bicentennial, donated by three anonymous benefactors. These bells are used on most Sundays and other significant occasions. The speakers for the bells are located in the bell tower.

Traditionally, swinging bells (the “ding-dong” type) were used to call people to church. The pealing bells, which involve two or more swinging bells, are associated with celebration. Their random, melodic sound signifies joy and festivity.

The tolling bells, on the other hand, are stationary bells struck by a heavy clapper, producing a stately and solemn sound. These bells have been used in times of mourning, such as during the days following the tragic events of September 11th, as a sign of respect and remembrance.

Statues and Art in the Sanctuary and Church

Over time, the statues in the sanctuary have changed. Photographs of the original plaster statues of the Sacred Heart of Jesus and the Blessed Virgin Mary in lifelike colors still exist. When the new statues were purchased, the old ones were given to parishioners.

Near the Blessed Sacrament altar, two hand-carved statues stand as a testament to faith and craftsmanship. These statues were purchased during the McGovern pastorate—locally sourced but imported from Italy. When they first arrived, they were lighter in color, but some resourceful parishioners stained them to the rich hue they display today.

When we acquired the Our Lady of Guadalupe painting, the alcove once reserved for St. Joseph was repurposed to make space for this new artwork. St. Joseph was then relocated to the sanctuary near the lectern. During the Christmas and Easter seasons, he is occasionally moved closer to the tabernacle to make room for the crèche and the baptismal font. Additionally, during St. Joseph’s Table, he is temporarily moved to the hall.

But why do we have statues in our churches? For centuries, statuary has served as a visual “textbook” for the faithful. Parents would bring their children into churches, using the art within to teach them about God, the life of Jesus, and the lives of the saints.

For many, these statues are more than just decorations—they are objects of devotion. People often find comfort and inspiration in praying before a statue of Jesus or one of the saints. A particularly notable custom is the inclusion of a statue of Mary during weddings. It is an optional, though popular, part of the ceremony to offer a prayer to Mary, asking for her help in being good parents. Often, the bride leaves a flower near her statue as a symbol of her devotion and petition.

Stained Glass Windows

Except for the Rose Window, the stained-glass windows in our church are not original. The original windows were simple pastel-colored glass panes. If you visit the sacristy, you can still see these original windows, offering a glimpse into the church’s earlier, more modest design.

For many years, there was considerable debate over the installation of stained-glass windows. Concerns ranged from financial feasibility to the impact on natural light. When the stained-glass windows were finally installed, the church still had its original chandeliers, though without the globes at the bottom. The globes were added in the 2000s to bring in more light.

The decision to commission the windows came after years of deliberation. Initially, there were plans to illustrate the Mysteries of the Rosary. However, it was later decided that the windows would instead feature beloved saints along the nave, with an intentional balance of men and women. Parishioners played an active role in selecting which saints would be depicted. Correspondence between Fr. McGovern and the studio in France details the thoughtful decisions and adjustments made throughout the process.

In 1962, the windows were completed at a total cost of $27,500, excluding the Rose Window. The windows were designed and crafted by the D’Alman Studio in France, with most of them signed by the artist M.S. J. Juteau.

The stained-glass windows encircle the church, beginning with the Rose Window and moving clockwise:

- St. John Vianney – Patron of parish priests, known for his humility, sacramental dedication, and profound spiritual influence.

- St. Pius X – Remembered for promoting frequent Holy Communion and liturgical reforms to make worship more accessible.

- St. Vincent de Paul – Patron of charitable works, symbolizing service to the poor and marginalized.

- St. Dominic – Founder of the Dominican Order and great advocate of the Rosary, depicted in a posture of teaching and prayer.

- St. Francis of Assisi – Embodying simplicity, love for creation, and Gospel-centered living.

- The Three Archangels: Michael, Gabriel, and Raphael – Representing protection, divine communication, and healing.

- The Nativity Scene – A cherished depiction of Christ’s birth, celebrating the Incarnation and God’s love for humanity.

- St. Peter – Holding the keys to the Kingdom, symbolizing the foundation of the Church and faithful leadership. It all depicts a roster reminding us to the threefold denial, and his own crucifixion.

- Christ the King – Shown in majesty and glory, affirming His eternal reign.

- Mary of the Rosary – Reflecting her role as intercessor and guide in deepening devotion to Christ through prayer.

- St. Paul – Honored for his missionary zeal and theological writings that continue to inspire the Church. The window also depicts his conversion as well as his martyrdom.

- The Ascension of Christ – Highlighting Jesus’ return to the Father and the promise of His eventual return; the eleven and Mary are looking at his Ascension.

- St. Vibiana – Patroness of the Archdiocese, representing the heritage and faith of the local Church.

- St. Frances Xavier Cabrini – The first American citizen canonized as a saint, known for her work with immigrants and the marginalized.

- St. Elizabeth Ann Seton – The first native-born American saint, celebrated for her contributions to Catholic education and the founding of the Sisters of Charity.

- St. Thérèse of the Infant Jesus (The Little Flower) – Inspiring many with her “little way” of love and trust in God.

- St. Teresa of Ávila – A Doctor of the Church, known for her mysticism, Carmelite reform, and spiritual writings.